.jpg)

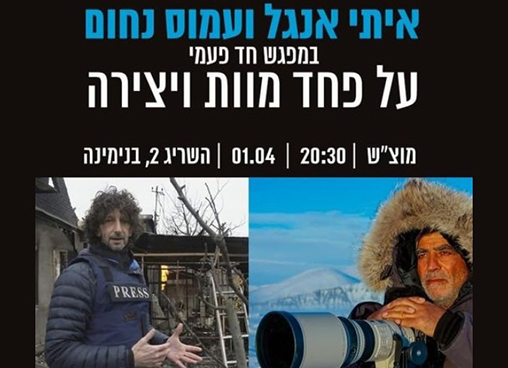

Meeting with Egyptian officials about Red Sea diving tourism and reef conservation March 1982

In 1971, the US Table Tennis team became the first American delegation to visit Beijing since 1949, ushering in a thaw in US-Chinese relations.

Through their shared interest in ping-pong, the Americans and Chinese took the first steps toward building trust, toward seeing one another as people rather than faceless enemies.

I hoped that through diving diplomacy, I could foster personal relationships between Israelis and Egyptians in the wake of the 1979 peace treaty. I also had a personal stake: The accord called for Israel to make a phased withdrawal from Sinai over the next three years. While I was excited about the prospect for peace, I was worried about the fate of Red Sea Divers in Sharm, not to mention the life Sharon and I had created for our growing family there. Moreover, I was concerned about the preservation of Sinai’s coral reefs, particularly Ras Mohammed.

.jpg)

Ras Mohamed at the tip of the Sinai, Egypt’s first nature reserve. (Photo by David Doubilet)

To be sure, diving diplomacy was a sideshow to the main event, but I take pride in my persistence in navigating perhaps the trickiest waters of my career. I did so as part of a group of Red Sea diving pioneers and explorers who worked together to transform a historic war zone into an international tourism destination. We pushed not only to protect one of the world’s most treasured marine environments, but to make it accessible to all. The experience was as frustrating as it was gratifying.

My three-year peace odyssey took me to Cairo three times, where I met with top Egyptian officials. It also took me to Jerusalem, where I was part of a group from Sharm who met with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. It had its farcical moments, such as when I joined a ragtag flotilla of Sharm settlers in a brief blockade of the Straits of Tiran, and its anxious ones, such as when a retired Israeli general and I were relaxing in a Cairo sauna when two other generals stepped in, both Egyptian.

Sadat meets the Shark Lady

I credit Dr. Eugenie (Genie) Clark, with kicking off diving diplomacy. Genie was known worldwide as the Shark Lady because of her pioneering research into the ocean’s apex predator. She was also a bestselling author and journalist for National Geographic magazine. Her connection with Sadat came through his son, Gamal, an enthusiastic diver whom she met at a photo contest in Cairo in December 1979. She did not realize who Gamal was until he invited her to his home, the presidential palace. As Genie enthused about the wonders of diving at Ras Mohammed, Gamal interrupted, “You have to tell my father about this.” He then left the room and returned with the president. The elder Sadat extended his hand to Genie and said, “You mean to tell me that I own the most beautiful reef in the world?”

Genie, who had learned fairly good Arabic while working on her doctorate in Egypt in 1951, regaled President Sadat with stories of dives off the Sinai. When she told him she was about to return to Ras Mohammed, he offered to put two of his cars at her service and arranged for several envoys to accompany her. That night, with childlike excitement, she called to tell me about the trip and ask that I help arrange for an Israeli contingent of scientists and environmentalists to meet her party.

I immediately contacted retired Admiral Yochai Ben-Nun, a former commander of the Israeli Navy. During the War of Independence, Yochai led the commando raid that sank the Egyptian flagship Emir Farouk, the wreckage of which I helped discover in 1972. Yochai, who had since become director of one of Israel’s largest oceanographic research centers, immediately agreed to send a top scientist to participate in the Egyptian-Israeli meetings.

On a December afternoon in 1979, I stood at the temporary border that ran from El Arish on the Mediterranean coast south to the southern tip of Sinai, established as part of Israel’s phased withdrawal of the peninsula. Illuminated by the sun setting over the mountains, Sadat’s Land Rovers approached with Genie and the Egyptian delegation. When they arrived, I jumped out of my Jeep and yelled, “Genie! Genie! Is that you?” She rushed over and gave me a big hug and a kiss on the check, no doubt surprising her Egyptian companions. We ushered the group over the border and for the first time in history, a meeting of colleagues took place: Egyptian and Israeli scientists led by the amazing Genie.

The following day, I gave the delegation a tour of Ras Mohammed, which Israel had established as the Sinai’s first marine nature reserve nearly a decade before. While none of the Egyptians explored the waters themselves, they were impressed by the rave reviews of the diving tourists they chatted with at the site. They learned from the Israeli scientists and conservationists all that had been done to protect the reefs.

The Egyptians’ visit was captured on film by a CBS news crew. I had tipped off correspondent Bob Simon, who was in Sharm covering the peace process and Israel’s pending withdrawal from the Sinai. Simon, reported on our efforts to preserve Ras Mohammed and its marine life. He also included interviews with Genie and her National Geographic team of David and Anne Doubilet, who were doing a shark feature for the magazine. www.youtube.com/watch?v=-p25T3Kbuu8 The more publicity the better.

.jpg)

Dr. Eugenie Clark (in red jacket) leads a delegation of Egyptian scientists over the interim border.

Genie’s trip opened the door for me to contact the Sadat family. I wrote letters to Sadat’s wife, Jihan, and to son Gamal to encourage their support of preserving Ras Mohammed as a diving destination. “[I]t is our most sincere dream that this area, along with any other nature reserve areas along these shores, will continue to be protected for the Egyptian people as well as the entire nature-loving people of the world,” I wrote in my letter to Mrs. Sadat. I offered to host both on a tour of Ras Mohammed.

The Egyptian scientists visit to Sharm lifted our hopes for future cooperation, only to have them dashed in late January 1980 when Egypt abruptly denied us access to the Ras Mohamed dive sites now under its sovereignty. The crown jewel of the Red Sea was just 400 meters away, on the other side of the interim border. I felt like Moses: The promised land within sight but out of reach.

1979 Blocking the Straits of Tiran

In 1956 and 1967, the Egyptians illegally blockaded the Straits of Tiran, the narrow international shipping passage that links the Israeli port city of Eilat with the rest of the world. Both times resulted in wars between Israel and its Arab neighbors.

There was a third closure that is much less known, and I was a part of it.

In fall 1979, Israeli residents of Sharm closed the Straits – well, for a few madcap hours, that is.

.jpg)

Straits of Tiran and Tiran Island photo by David Doubilet

Unlike the settlers of the Israeli-built town of Yamit in northern Sinai, Sharm residents were not as extreme in protesting the peace treaty itself. Many of us felt making peace with our most dangerous enemy was worth the price, even if it included abandoning the lives we had established in Sinai. Indeed, when rabblerousers from Yamit and the West Bank territories tried to stir up opposition in Sharm, we had little to do with them and they turned heel and went back to from where they came.

With the final withdrawal two and a half years away, our big beef with the government was an economic not political one. The government had barely begun serious discussions with us about the financial implications of the withdrawal. Compensation talks were already well underway with Yamit and northern Sinai agricultural settlements. We felt ignored, perhaps because we had not kicked up a fuss.

Among our questions: Would any of us be allowed to stay? Would evacuated residents and business owners be compensated for their business and personal relocation costs? Would housing be offered to the uprooted inside the pre-1967 borders?

An ad hoc group of residents held a meeting and out of it came the decision to block the Straits. Before dawn on November 11, 1979, a ragtag armada of diving and pleasure boats headed to the Straits. We secured a rope that connected oil drums serving as floats to the light tower on Gordon reef, with the intention of tying the other end to the Ras Nasrani light tower on the Sinai side of the straits. In theory, it seemed like a great idea. In reality, it turned into a comedy of errors. The rope, besides being unwieldy, was too short. Strengthening winds whipped up the waters in the narrow passage. Within minutes, many of the blockaders became seasick, and some feared their boats would capsize. We were also spotted by an Israeli Air Force plane, which reported to base about our suspicious activities.

Realizing our plan for the rope was doomed, we fell back on Plan B. One of the dive center vessels, trying out a new VHF marine band radio, sent out a message over the emergency radio channel 16. In several languages, it warned approaching ships not to enter the straits. A cargo ship heading down from the Jordanian port of Aqaba radioed back, asking what was going on. We responded that the straits were closed. The Israeli Navy picked up the exchange and notified us that we were violating international law. It dispatched a patrol boat to break up the demonstration. Overhead, though, a reporter was sending live reports to one of Israeli’s most popular radio stations, having chartered a plane after we tipped the media off to the blockade plans. That got Jerusalem’s attention.

We called off the protest after learning that the prime minister’s office had invited a Sharm delegation to a meeting in Jerusalem. Maybe it was just a coincidence, but we think our demonstration succeeded as a wake-up call. It also showed that a $75 marine radio could effectively close the Straits of Tiran. Unlike the Egyptians, we did not need cannons and warships.

A disaster in the making

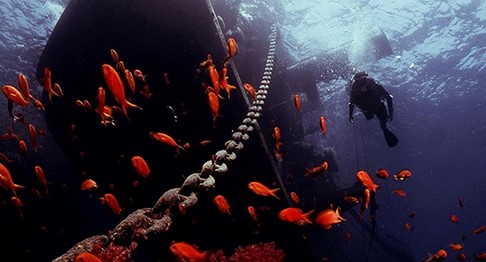

Matters went from bad to worse on April 1, 1980, when the coastal freighter Jolanda went aground at Ras Mohammed. The Israeli Navy tipped me off the morning of the grounding. Standing in my front yard, I could see the stranded ship through my binoculars. I was anxious to get our dive team there to survey the damage and assess how it could be contained, but we first needed permission from the Egyptian authorities.

I immediately called my friend and Scuba diving student, Sam Lewis, the American ambassador to Israel. Whenever he could, Sam – as he asked us to call him – would break away from his responsibilities to dive with us in Sharm. In response to my request for help, he contacted the embassy in Cairo. Within 24 hours, Egypt gave us the go ahead. I gathered members of my team, and we took a dive boat to the scene the next morning.

Reefs are built by colonies of soft and hard corals so fragile that even a diver’s fin can break them. The Jolanda was wedged atop the northern coral island at Ras Mohammed’s Shark Reef. Its captain compounded the damage when he tried to dislodge the vessel at high tide. More corals were shattered when the ship dropped its large anchor on the shallow seabed. A bizarre array of cargo was strewn about the shallows, from industrial plastic sheeting to porcelain toilets to a new BMW, stuck head down between the islands.

Jolanda anchor chain sitting on the reef at Ras Mohammed. (Photo by David Doubilet)

When we arrived, a salvage vessel, the Montagne, had already dropped anchor atop a beautiful coral head that may have taken centuries to reach its size and majesty. Salvage operators are paid based on what they retrieve, popularly called a “no cure, no pay” agreement. As they let loose their chains and ropes, reef preservation is the farthest thing from their minds.

I photographed the scene both above and below water, documenting the damage to the reef. Back at the dive center, I contacted the American Embassy in Tel Aviv about the disaster in the making. My mission had shifted, from getting dive access to Ras Mohammed to saving the natural wonder itself.

Top US diplomats swung into action – Ambassador Lewis in Tel Aviv, Ambassador Alfred “Roy” Atherton in Cairo, and Assistant Secretary of State Nick Veliotes in Washington – and Egypt halted the salvage operation within days.

The Swedish captain of the Montagne, a huge guy, was angered by our interference to the point of threatening my life. I first encountered him when I came up from my initial dive. Towering over me in an inflatable boat, he asked me what I was doing on his wreck. When he revved his outboard engine ominously in my direction, I quickly dove back down and navigated at depth toward the safety of our boat on the other side of the reef. At one point, the captain threatened me with physical harm if I returned to the wreck site.

.jpg)

Surveying the damage done by the Jolanda wreck.

After the Egyptian authorities expelled him from the Jolanda wreck site, the captain decided to see what he could salvage from the Dunraven, the nearby sunken wreck we had discovered three years before. Leaving the Montagne anchored above, he dived into the wreck, never to be seen again. Ironically, the Israeli and Egyptian authorities enlisted me to search for his body – this just days after he had wanted me dead.

I combed Dunraven’s maze of silt-filled passageways, cabins, communal areas, and cargo holds to no avail. Perhaps the captain had become stuck trying to squeeze through a narrow passage. Or, since the ship rested upside down, he might have become disoriented and run out of air trying to find his way out.

Over the next six years, Ras Mohammed absorbed the Jolanda, which essentially became an appendage to the reef that sank her. Coral colonies attached themselves to every available space on the submerged part of the wreck. Then, in 1986, a fierce storm dislodged the ship from its shallow perch, sending it 200 meters down to the base of Ras Mohammed. Among the remnants in the shallows are a few of the toilets. The “rest stop” attracts divers eager to pose for underwater photos on the coral-encrusted thrones.

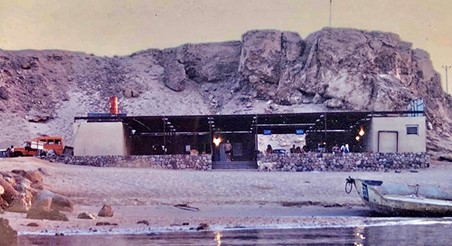

Once the immediate crisis over the Jolanda was over, Egypt reimposed its restrictions on Ras Mohammed, and we resumed our fight to have them lifted. Once again, we turned to the good offices of ambassadors Lewis and Atherton. By May 15 the American diplomats helped to persuade the reluctant Egyptians into allowing sea, though not land, access to Ras Mohammed – and even that was restricted to the 10 or so dive boats based in Sharm, half of which belonged to our Red Sea Divers fleet.

Instead of being able to freely come and go as we had in the past, we had to present a list of crew and guests, along with their passports, to an Israeli official in Sharm each day by a certain hour. The official would then drive to the temporary border, where a tent had been set up for him to hand over the documents to his Egyptian counterpart. After reviewing the documents and stamping the passenger list, the Egyptian would issue one-day permits for diving the next day. Although the process was cumbersome, it marked perhaps the first time that Israelis and Egyptians on either side of the border engaged in problem solving as neighbors, rather than enemies.

.jpg)

Interim border at Ras Mohammed where we had our diving visas stamped.

But to us, what mattered most was that we could again offer dive tours to Ras Mohammed and that it was still being protected. We succeeded, for example, in helping to stop Egyptian fishermen from using dynamite to stun or kill schools of fish, devastating other marine life and the coral reefs in the process. We photographed fish and corals mutilated by the explosions and shared the images with the Israeli and American authorities. They, in turn, pressed Egyptian officials to put an end to the dynamiting.

.jpg)

Fishing with explosives at Ras Mohammed.

My first trip to Cairo

Hoping to continue with diving tourism in Sinai after the Israeli withdrawal, I seized on an opportunity to visit Egypt in December 1980. One of our customers, a South African businessman, organized two days of meetings for me with Egyptian tourism officials and potential business partners. At the time, there were no direct flights between Israel and Egypt; in fact, Egypt still did not allow Israeli nationals into the country aside from official representatives involved in the peace process. I was able to circumvent those barriers by flying to Cairo via Athens and using my American passport. I was met at the airport by a driver/escort sent by my Egyptian host, the Marinjac Company.

In the relatively short limo drive from the airport to my hotel, I was struck by the crowds of people, on foot and in cars. Back then, Cairo’s population alone was nearly twice that of Israel as a whole. Traffic was chaotic, despite a large presence of police and soldiers armed with automatic weapons mounted with bayonets. As we banged along the pot-holed roads, blaring horns were a constant soundtrack. I timed the longest honk-free period at eight seconds. By the time I arrived at my hotel, I could hardly hear myself think. It was in Heliopolis, an affluent suburb of Cairo and home to the Marinjac Company.

The next morning at breakfast I met up with my colleague from South Africa. We prepared for our meeting with Marinjac chairman Khalifa Zarrugh, an entrepreneur and political exile of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Khalifa, who was in his 50s, went by the moniker Haj, a title given to Muslims who have made the pilgrimage to Mecca.

His company was a conglomerate that sought to reach beyond its warehouses along the Suez Canal. Haj Khalifa was interested in investing in hotels and tourism in the soon to be repatriated Sinai, including in my diving operation. We met directly only twice, but he assigned one of his top aides to introduce my South African colleague and me to

Egyptian officials, including the national prime minister. I was always identified as an American expert and entrepreneur, my Israeli citizenship left unmentioned.

The Egyptians questioned me about the prospects for diving tourism. I responded that the Sinai could become a major international tourism destination and urged the business leaders to seize the chance to get in on the ground floor. At Haj Khalifa’s request, I drafted a business plan for a diving resort, hotel, and fleet of vessels and vehicles to transport the guests to and from the diving sites. We kept in touch for a year afterward, but the plan never came to fruition.

The business side of the trip concluded, I traveled to the Red Sea port towns of Hurghada and Safaga for a first-hand look at Egypt’s diving tourism, which was still in its infancy. I stayed at the Sheraton Hurghada, then the nicest hotel in the area. I was struck by the plaque at the entrance: “This hotel was recently refurbished, having received extensive damage in the October War to Liberate Sinai,” referring to the 1973 Yom Kippur War. I wondered if I was the first Israeli to stay there; I used my American passport to check in.

.jpg)

Sheraton Hurghada, refurbished after damage from 1973 Yom Kippur War.

The next day I was the guest of the Club Med south of the city. The resort’s French diving staff invited me to explore the waters off nearby Giftun Island. They took me down 70 meters, a bit too deep for safety I thought, but maybe that was a way to show off their

skills. In return for their hospitality, I gave a slide show about diving in the Sinai to hundreds of guests, staff, and local officials.

In Genie’s footsteps

Before leaving Hurghada, I had one last stop to make, a nostalgic one. I felt I owed it to my mentor Eugenie Clark to visit the research center where she had spent 1951 working on her doctorate under Professor Hamed Gohar, the dean of Egypt’s marine biologists. Perched aside the Red Sea, the center appeared forlorn and abandoned. After finding it locked, I was heading back to my taxi when a watchman appeared with a bunch of keys. He spoke broken English and I even poorer Arabic. I managed to convey that I wanted to see inside the place where my friend had lived and worked 30 years before. The watchman picked a key and unlocked the large front door.

With a creaking sound right out of a horror movie, the door opened to what appeared to be a lab entombed in time. Under the dust and tangled in cobwebs were jars of marine species in formaldehyde. I wondered if some had been collected by Genie herself. By the entrance stood two large stuffed dugongs, native to the area and cousins to the Florida manatee. Thrilled to play the role of tour guide, the watchman showed me the biological differences between their genders.

I left with mixed emotions, excited to have walked in the footsteps of Genie and of Professor Gohar, saddened that the research station had fallen into such a dilapidated state. In recent years, the center has been totally renovated and, judging by photos I have seen, looks nothing like what I remember.

I had to pinch myself each day during my week in Egypt, as I thought about being in the nation that had fought four devasting wars with my adopted country. But despite that history, I felt intoxicated by the feeling that peace was becoming a reality, and I could play a role in helping it along.

Keeping cool in a sauna

For my next trip to Cairo, in late October 1981, I went not as an independent operator using an American passport, but as a member of an Israeli delegation.

By this time, the Egyptians and Israelis were holding a series of talks between teams representing corresponding government ministries. In recognition of the importance of diving tourism to Sinai, Israel’s Ministry of Tourism invited the Israeli Diving Federation to participate as advisors in the bilateral tourism talks. The federation selected its chairman, retired IDF Brigadier General Shaul Givoli, to represent its activities and me as the representative of the Israeli dive travel industry.

With a great sense of excitement, we boarded a pair of chartered buses at Habima Square in Tel Aviv at 7 a.m. for a direct trip to Cairo. The delegation was led by the minister of tourism, Avraham Sharir, accompanied by officials and entrepreneurs with interests in all aspects of tourism, including transportation, services, and accommodations.

.jpg)

Israeli bilateral tourism delegation heading to Cairo October 1981.

When we arrived at the temporary border crossing near El Arish on the Mediterranean coast of Sinai, we were met by the members of the Egyptian delegation to the talks. As official guests of the Egyptian government, we were whisked through the crossing. We then traveled another several hours to the Suez Canal. The scene of a pitched battle during the 1973 Yom Kippur war, the canal zone was now bustling with people, vehicles, and a menage of four-legged traffic including donkeys and camels. We crossed the canal on a ferry and drove another two and a half hours to Cairo.

At the Cairo Hilton, the desk clerk winked at me as he handed over an envelope with my room key. I was puzzled by his gesture until I noticed that the envelope was addressed to Mr. Mohamed Rosenstein. I guess the clerk thought I was a fellow Moslem, even with my very un-Moslem last name! I have no idea how I ended up with it. Who knows? Maybe I was the victim of an Israeli colleague’s mischievous sense of humor.

Exhausted and sore after the nine-plus hour bus ride, I decided to take advantage of the hotel’s spa. As Shaul, the federation leader, was staying in the adjacent room, I invited him to join me. Shaul and I had been friends since his days in active service when he would dive at my centers. As a general, he headed the army’s educational and training programs. After he retired, he became a high-ranking police officer. But there was nothing officious about him; he was friendly with a terrific sense of humor.

After checking into the spa, we changed into robes and hit the spacious sauna. There, we reviewed the day’s events, but stuck to English to avoid drawing attention to ourselves. After a few minutes, two tall Egyptian men who appeared to be in their late 50s, walked in and took the bench opposite ours. We got to chatting. They welcomed us to Cairo and asked what had brought us to Egypt. Hesitatingly, I said that we were members of a delegation to the peace negotiations between Egypt and Israel. Silence. I immediately regretted my honesty, knowing that not all Egyptians embraced President Anwar Sadat’s initiative. But a few seconds later, the men smiled and said that they totally supported the treaty. They said they had had enough of war between our nations. I breathed a sigh of hot sauna air in relief.

Then one of the Egyptians extended his hand and introduced himself as General Ahmed and his friend as General Mohamed. I almost fainted. Here, on our first day in Cairo, we two Israelis found ourselves in a sauna with two Egyptian generals. I glanced at Shaul, who sensed my uncertainty but also my curiosity. He nodded toward me, which I took as a sign that it was OK to talk more about ourselves. I told the generals that I was Howard, a businessman from Sinai, and that my colleague was Shaul, head of the Israeli Diving Federation. The ice now broken in that very hot room, I savored the symbolism of the moment: I was sitting with three generals, two of them Egyptian and the third Israeli. Less than a decade ago, they were bitter enemies. Today, they were sharing a sauna, each dressed in the same simple uniform of a towel across the lap. To all appearances, we were four ordinary guys schmoozing. But for me, it was a glimmer of the promise of peace to come. I had a sense that my battle-weary companions felt the same way.

Paying homage to Sadat

We arrived in Cairo at a time when the treaty appeared in possible peril. Three weeks before members of the Islamic Jihad had assassinated President Sadat as he watched a parade commemorating Egyptian valor during the October 1973 war. Our first official stop was the site of Sadat’s grave. He was buried at the pyramid-shaped Unknown Soldier Memorial, near the reviewing stand where he had been shot.

Just a five months before I had photographed this great man, buoyant and beaming, as he arrived in Sharm el Sheikh for a summit with Prime Minister Begin. Would his successor, Hosni Mubarak, maintain the momentum toward peace? As to Sinai, would Mubarak share Sadat’s commitment to protecting Ras Mohammed?

.jpg)

President Anwar Sadat meets Prime Minister Begin in Sharm, June 4, 1981.

.jpg)

Egyptian Unknown Soldier Memorial, where Sadat was assassinated on Oct. 6, 1981, and where he was buried four days later.

Winning over the Egyptians

That first full day in Cairo was showtime for me, with day and evening slide shows on my agenda. The first was at the internationally renowned Mena House Hotel, Sadat’s designated place for discussions with Israeli leaders and the site of the bilateral tourism talks.

In my decade-long career, I had made numerous presentations on Red Sea diving all over the world. But this one was different. I felt the future of Sinai diving was at stake. Egypt had yet to divulge its plans for the region. Would it revert to its pre-1967 status as a virtual armed camp, populated only by soldiers and Bedouins, or would its natural treasures be preserved for all the world to see? I faced a tough audience: government ministers, military leaders, and senior bureaucrats. I doubted if any of them had ever strapped on a scuba tank.

.jpg)

At the October 1981 tourism talks in Cairo (from left): Egypt’s minister of tourism, Ali Jamal Al-Nazerm;

his Israeli counterpart, Avraham Sharir; and the director general of Israel’s tourism ministry, Rafi Farber.

I wanted to stress two points in my talk: first, that diving could be the backbone of a prosperous tourism industry in the Sinai and, second, that everything depended on Egypt retaining the stringent rules Israel enacted to protect the fragile ecology. I also recognized that I had to grab the attention of my listeners from the start and keep them riveted. In other words, to influence them, I had to keep them entertained. After some thought, I came up with this opening: “Tourists will pay a lot of money to swim with sharks.” That caught their attention. I followed up with slides showing the extraordinary beauty of the Sinai, from the mountains to the depths of the Red Sea.

Judging by the applause and questions, the presentation was a success – so much so that officials from the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism invited me to a meeting the next day at which they asked if I would be interested in continuing to run my Red Sea Divers center after the Israeli withdrawal. I was the only Israeli operator to receive such an invitation, most likely because of my American citizenship. The officials even presented me with a draft contract. But while I seriously considered the offer, I was not prepared to abandon the life I had made in Israel.

After the Mena House lecture, I met with the American ambassador to Egypt, Roy Atherton, a good friend of Ambassador Sam Lewis in Tel Aviv. Sam, a staunch proponent of diving diplomacy, had set up meetings for me with influential US diplomats in Cairo. Atherton was polite, professional, and asked all the right questions. He pledged to provide whatever support he could.

Winning over the divers

The ambassador had already arranged for me to give a slide presentation that evening at the US Cultural Center in Cairo. This time the audience was stacked in my favor. The center’s staff went out of its way to invite Egypt’s diving elite, tourist professionals, and interested academics. I began my talk with an appeal to my fellow divers: “You are about to return to one of the most beautiful diving locations in the world. It is up to you to protect it against those who would exploit and even harm it.”

Ras Mohamed coral reef, among the richest and most beautiful in the world.

With US Ambassador W Samuel Lewis.

Getting the Israeli officials on board went smoothly, not so the Egyptians. Back then, it was difficult for Egyptian nationals to obtain travel permits to Israel; indeed, 40 years later, it is still hard.

When Ayman told me his government was less than cooperative, I again turned to Sam, who contacted his counterparts in Cairo. They succeeded in obtaining a special permit for Ayman to visit Israel accompanied by a staff member of the US Embassy in Cairo.

A temporary border crossing had been established just west of Ras Mohammed. After coordinating our plans with the military, which controlled the area, I arrived on the Israel side in early March 1982. After a few minutes of bureaucracy, the checkpoint barrier was raised and Ayman and his embassy escort walked through, diving gear and suitcases in hand. We embraced like childhood friends, climbed into my jeep, and off we went.

We dived together for a few days, and Ayman charmed the invited group of elite Israeli divers. Sharon prepared a lovely home-cooked meal, capped by a chocolate cake with the flags of both countries and the inscription “Shalom” on it.

With me at Ras Mohammed: Ayman Taher and Dr. Eugenie Clark. (Photo by Amos Nachoum)

Stephanie Sagebiel, who was my liaison at the American Embassy in Cairo sent me a cable after Ayman returned to Cairo, relaying his excitement about the sites he had visited and how moved he was by our hospitality. She said that he had recommended to the minister of tourism that the Egyptians taking over Sharm’s diving centers work with operations like mine during the transition period and possibly beyond. Sadly, that did not happen.

Goodbye, Sharm

Na’ama Bay 1982 at the time of the Israel withdrawal from the Sinai.

By March 1982, Israeli civilians started packing up to leave the Sinai. We all had to be out by mid-April. Only Israeli officials and military could remain until April 25, when Egypt regained complete control of the region.

Some of us had been living in Sharm for a decade or more. We supported the peace process, even though we were about to pay a high price, both personally and professionally, with the upcoming withdrawal from Sinai. All Sharm turned out for the tearful ceremony when we lowered the Israeli flag at our school for the last time. Just about everyone knew each other in this small, tight-knit community. Now we were about to disperse all over Israel and beyond. Some families would break up under the strain and tension brought about by the relocation.

April 1982: Lowering the Israeli flag for the last time in Sharm el Sheikh.

By then, Sharon and I were living in a tiny two-bedroom prefab house, with a front-yard view of Ras Mohammed. We had three children, Ayelet, who was 8 and among the first Israeli children in Sharm; Nadav, who was 6; and Daria, who was 4 and a half. They had spent their infant years crawling on the beach and splashing in the turquoise waters of the bay – or fast asleep in a shaded playpen next to the diving center. They were not happy about leaving Sharm, especially their school and Bedouin friends.

The Egyptian government set up its own entity, the Overseas Company, to purchase and manage Israeli-owned tourism businesses, including dive centers, motels, and tourist villages like Neviot (Nuweiba) and DiZahav (Dahab). The Israeli government set up a special committee of army officers to assess the value of our businesses and negotiate with the Overseas Company. Fortunately, the Egyptians accepted the prices we requested, avoiding delays that no one wanted.

The 200th tank

The week before my departure, an Egyptian team visited the dive center to verify our inventory list, which we had prepared well in advance. The team’s accountant was very thorough. We had listed 200 diving tanks; he counted 199. We had to scramble to find one more tank, as if one scuba tank might derail the peace treaty or at least our sale of the diving center. Thinking quickly, I ran to my office and retrieved a fire extinguisher. I placed it down with the other tanks. When the accountant asked why the 200th tank was red when all the others were yellow, I calmly explained that it was my personal tank. We were lucky he was not a diver.

Red Sea Divers Center, Na’ama Bay, Sharm el Sheikh.

After the inventory inspection was completed, we sat down at one of the large tables in our patio restaurant for a signing ceremony. Noticing my partner Yossi pealing an apple with a fancy Swiss army knife, the chief Egyptian negotiator, Admiral Haluda, asked if the knife was part of the inventory. The query caught Yossi off guard, and he did not know what to say. After I kicked his ankle under the table, he came up with the right answer. He smiled at the admiral and nodded yes. The deal was done!

Bedouin staff from the diving center helped Sharon and me pack up our belongings and load them onto a truck bound for our new home in Israel. The Bedouins were like family to us. We sometimes employed three generations from the same family: a grandfather, son, and grandson. Wonderful and loyal workers, the Bedouins seemed as sad as we were about our leaving.

Time to pack up and leave Sharm.

We almost forgot Saya, our shaggy rescue dog. With all the hustle and bustle of packing and getting the family to the airport for the flight to Tel Aviv, we left Saya behind. I returned to our home to pick her up before heading to Israel in our beat-up Mercedes. It was my last departure from Israeli-administered Sinai, but not the last time I would be making the scenic drive along the Sinai Peninsula.

After living for so many years in a remote wilderness, we did not want to move to one of Israel’s bustling, noisy cities. We found a home in Hofit, a pastoral village of 200 families along the Mediterranean coast 40 kilometers north of Tel Aviv. A stream runs through our backyard, which borders on a nature reserve. We can see the sun set on the Mediterranean half a kilometer away. Neighbors in Sharm who live part of the year in Hofit tipped us off that the house was on the market. Our fourth child, Ariel, was born three years after we left Sharm; he has never forgiven us for missing out on the Sinai experience.

Back to Cairo

Though we had moved back to Israel, I still saw my future in Red Sea diving. I had been closely involved as a consultant to the peace deal’s bilateral tourism agreements, which ensured that Israeli divers would have access to the waters around Sinai reefs.

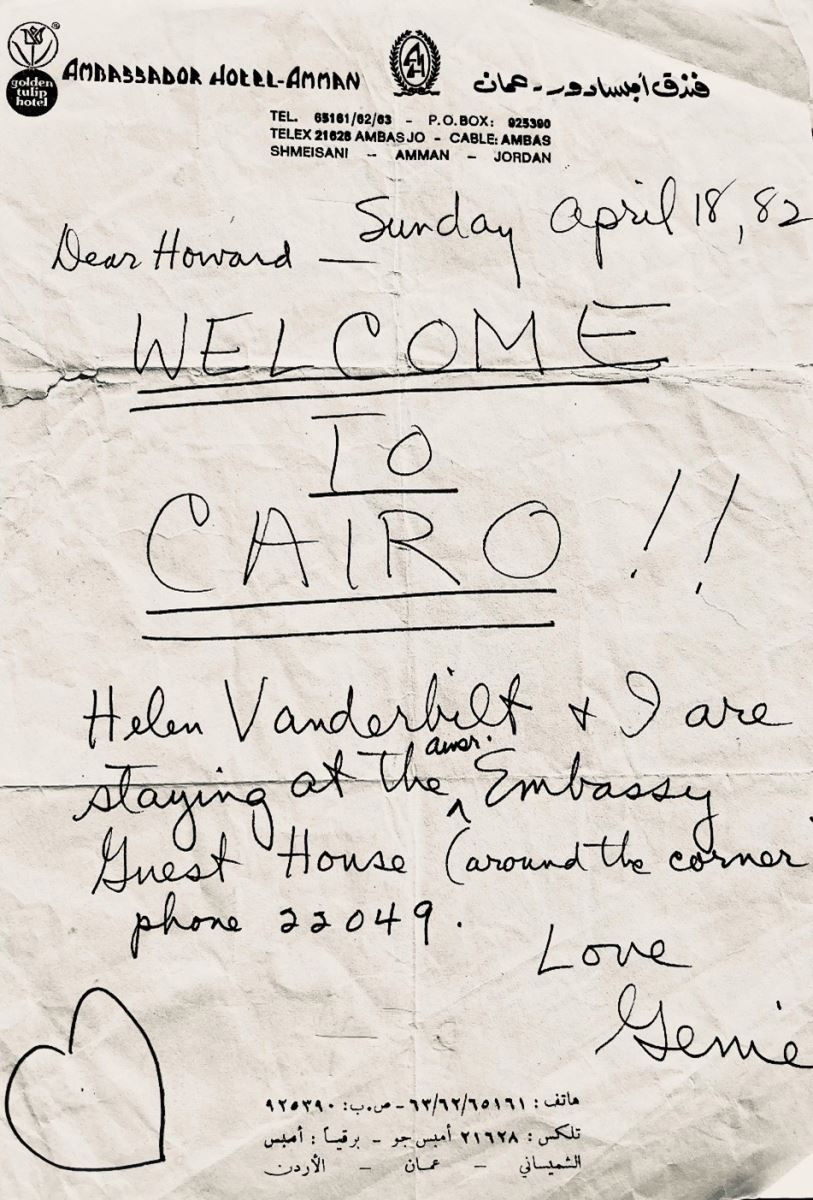

Less than a week after we moved into our new home, I flew to Cairo to sound out the Egyptians on ways I could stay in business. This time, I did not have to go via Athens. El Al, Israel’s national airline, now had direct flights to Cairo, which took less than an hour from Tel Aviv. This being my third trip to Cairo, I no longer felt like a stranger. I had contacts among the Egyptian public and private sectors and in the American embassy.

To my delight, my old friend Genie Clark was in town to talk with Egyptian officials about the nature reserve at Ras Mohammed, which she helped initiate in talks with Anwar Sadat in late 1979. She and her friend and benefactor Helen Vanderbilt were staying at the US Embassy guesthouse. Helen’s family sponsored Genie’s marine lab in Sarasota, Florida, which today is known as the Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium. The US ambassador, Roy Atherton, invited Genie, Helen, and me to social events, where I could hobnob with the Egyptian elite. He also helped me set up meetings with government officials.

Welcome note from Genie Clark when I returned to Cairo.

Penetrating the Egyptian bureaucracy required vast reservoirs of patience. I spent many hours cooling my heels, waiting for meetings in antiquated offices. The Egyptians I met were generally very courteous, although they tended to tell me what they thought I wanted to hear, which was usually the opposite of what transpired.

I also met with my diving friend Ayman Taher about a possible joint venture. As a member of a prominent Egyptian family, Ayman helped me secure appointments with tourism officials, the new military governor of Sinai, and well-placed leaders of the Egyptian diving community. They asked me about my experiences, the diving conditions around Sharm, and the best sites to explore.

At that time, Sharm’s tourist infrastructure amounted to little more than one hotel, the Israeli-built Marina Sharm, which was next door to my old Red Sea Divers center; the Clifftop motel; a youth hostel; and a nature society field school with spartan accommodations. I proposed the idea of a fleet of floating hotels as an interim solution for accommodating visiting divers. I wanted to tap into the emerging market of Liveaboard cruises, which were gaining popularity in the Caribbean and Australia.

While I did not make any deals during my five days in Cairo, I did obtain a provisional license to operate a diving boat in the Sinai region of the Egyptian Red Sea. Now the challenge was finding suitable vessels to transform into floating hotels.

Ayman and I did not realize our hopes for a joint venture, but at my recommendation, he invested in a stretch of land in Sharm that turned into a commercial gold mine.

A living legacy

The cooperative arrangements I had hoped for with Egyptian divers never materialized. The Egyptians instead relied on experts from Europe, rather than Israel.

Thanks in part to compensation I received from the Israeli government, I purchased my first Liveaboard diving yacht, Gabriella. Renaming it Fantasea 1,

I launched Fantasea Cruises Ltd. toward the end of 1982. We offered diving excursions to the Egyptian Red Sea for the next 15 years. By the mid-1990s, though, the Egyptians had built up their own operations and began crowding us out. Ultimately, with high fees and red tape, the Egyptian authorities made it nearly impossible for foreign operators like me, despite my 25-year history in the area.

Fantasea 1 Live Aboard at Marsa Bareka anchorage

So, what did diving diplomacy accomplish? It helped secure a provision in the peace treaty for a special visa to Sinai that allows thousands of Israelis to visit and dive there each year. Most importantly, it helped pave the way for Ras Mohammed to be declared Egypt’s first national park and nature reserve.

Peace finally comes to the Sinai.